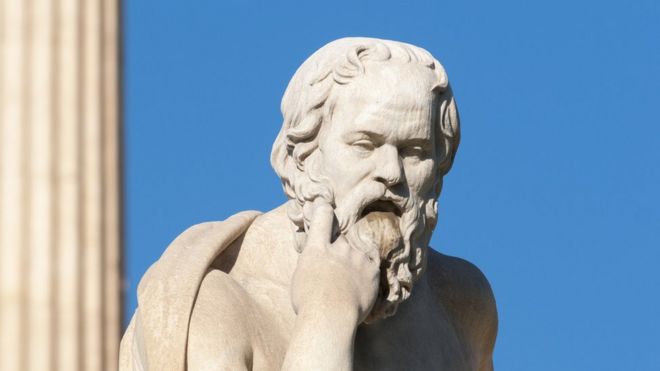

The classical Greek philosopher Socrates believed the ideal house should be warm in winter and cool in summer. With clarity of thought like that, it’s easy to see how the great man got his reputation.

At the time, such a desire was easier to state than to achieve, yet many pre-modern civilisations designed buildings to capture sunlight from the low-hanging winter sun, while maximising shade in the summer.

All very elegant but that’s not the sort of solar power that will run a modern industrial economy. And millennia went by without much progress.

A Golden Thread, a history of our relationship with the sun published in 1980, celebrates clever uses of solar architecture and technology across the centuries, and urged modern economies wracked by the oil shocks of the 1970s to learn from the wisdom of the ancients.

For example, parabolic mirrors – used in China 3,000 years ago – could focus the Sun’s rays to grill meat.

Solar thermal systems used winter sun to warm air or water that could reduce heating bills.

Such systems now meet about 1% of global energy demand for heating. It’s better than nothing, but hardly a solar revolution.

A Golden Thread only briefly mentions what was, in 1980, a niche technology: the solar photovoltaic (PV) cell, which uses sunlight to generate electricity.

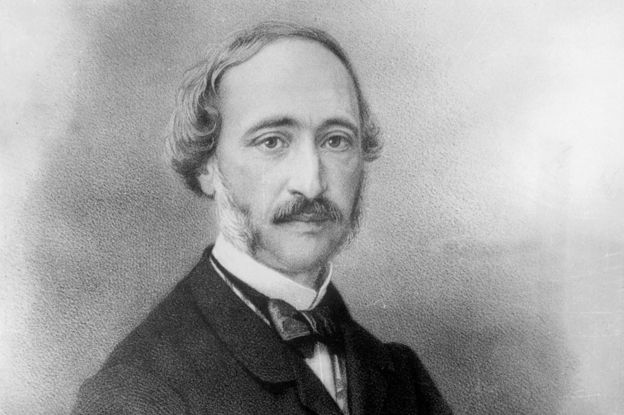

The photovoltaic effect isn’t new. It was discovered in 1839 by French scientist Edmond Becquerel, when he was just 19.

In 1883, American engineer Charles Fritts built the first solid-state photovoltaic cells, and then the first rooftop solar array which combined different cells, in New York city.

These early cells – made from a costly element named selenium – were expensive and inefficient.

The physicists of the day had no real idea how they worked – that required the insight of a fellow named Albert Einstein in 1905.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme’s sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

But it wasn’t until 1954 that scientists at Bell Labs in the US made a serendipitous breakthrough.

By pure luck, they noticed that when silicon components were exposed to sunlight, they started generating an electric current. Unlike selenium, silicon is cheap – and Bell Labs’ researchers reckoned it was also 15 times more efficient.

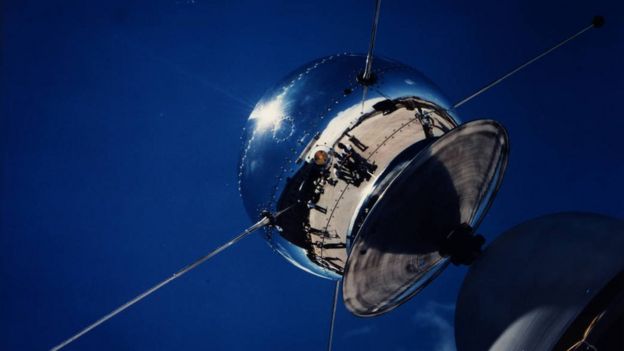

These new silicon PV cells were great for satellites – the American satellite Vanguard 1 was the first to use them, carrying six solar panels into orbit in 1958.

The Sun always shines in space, and what else are you going to use to power a multimillion-dollar satellite, anyway? Yet solar PV had few heavy-duty applications on Earth itself: it was still far too costly.

Vanguard 1’s solar panels produced half a watt at a cost of countless thousands of dollars.

By the mid-1970s solar panels were down to $100 (£81) a watt – but that still meant $10,000 for enough panels to power a light bulb. Yet the cost kept dropping.

By 2016 it was 50 cents a watt and still falling fast. After millennia of slow progress, things have accelerated very suddenly.

Perhaps we should have seen this acceleration coming.